Last week I competed again in the annual US Cyber Open CTF. This is a ctf run every year by the US Cyber Team where individuals compete both for prizes and as a way to stand out if you are applying for the US Cyber Combine, where the next seasons team will be picked. Last year I successfully made the US Cyber Team, and although I unfortuneatly won’t have enough time to do again for Season IV, I still wanted to compete. I didn’t have as much time as I would’ve wanted for this CTF because it clashed with a couple vacations, but I ended up getting a few solid days of work and finished top 20. This was one of the crypto challenges that im pretty sure I didn’t solve the intended way, but the highlight of this solve is that I finally learned how to write a multi-threaded python program.

Limitless Learning Links

Description

A simple ECC problem.

Solution

Problem Analysis

We are given two files, one is the chall2.sage file. This is a sage script, which is a python based mathmatics programming language.

from Crypto.Util.number import getPrime

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

import random

import os

import hashlib

flag = b"SIVUSCG{REDACTED}"

p = getPrime(256)

a = random.randint(2024, 2^32)

b = random.randint(2024, a)

F = GF(p)

E = EllipticCurve(F, [a, b])

G = list(E.gens()[0])[:2]

print(f"{G = }")

secret = (str(a) + str(b)).encode()

key = hashlib.sha256(secret).digest()[:16]

iv = os.urandom(16)

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv=iv)

ct = iv + cipher.encrypt(pad(flag, 16))

print(f"{p = }")

print(f"{ct = }")

We are also given output4.txt which shows the output of the program.

G = [47955680961873936976498017250517754087050557384283400732143179213184250507270, 29032426704946836093200696288262246197660493082656478242711220086643009788423]

p = 61858486249019152861579012404896413787226732625798419511000717349447821289579

ct = b"\x18\xf4$\xf1\xe5WA[\xf2P\xfa\xfcEE\t\xed\xe2m\xaf\xf6$K\xf6\xae\xd9K\x81\x95D\xe3`W\x8f\x04\xfbI\xe5\x06\xd3\xe9\x1a\x1e\x16\xfbZ\xe6\xd2\x06\xd6o|#ns'm\x12\x96\x1d\x8d\xd1\xbd<\xd9\x1dy\x0b\xa95i\xfds\x86|\xad\x92\x88\xa7\x07="

As the description mentions, this challenge is based on ECC, which stands for elliptic curve cryptography. In this case the flag is encrypted with AES (American Encryption Standard), but the real challenge here is to recover the variable secret. If we get that, we can just calculate the key and decrypt the flag like normal. As for the ECC part of the challenge, they generate an elliptic curve equation using the sage builtin EllipticCurve. They then take a generator point for that curve, G, and give us the x coordinate of that point. We also get p, which is the prime generated for the Galois Field and ct which is just the AES encrypted flag.

What Does Any Of It Mean!?!?

I am not very well versed in ECC, which is probably why I couldn’t solve this in the inteded fashion, but I did learn a fair bit researching for this challenge. Im going to give a breif summary of the relevant information I used for this challenge, but if you are already familiar with this stuff, the more specific solution part of the writeup will be a bit further down. The wiki page actually does a pretty good job at explaining the basics for someone who has taken one or two semesters of general discrete mathematics and wants more detail as well. The basis for ECC is the Discrete Log Problem (DLP). This is a type of mathematical problem that is REALLY hard for computers to solve. Its considered secure because if big enough numbers are used, getting a computer to solve the problem would take multiple times the age of the universe. This ultimately is because as far as we know, the best way to solve the DLP isn’t much better than just guessing a random number and checking if it is correct. The reason any of this works is because these elliptic curves aren’t like typical curves you might study in high school algebra or calculus. In those areas of math, all equations are taken over the real numbers, which essentially means we are using the classic number line we know and love. 2 + 2 = 4, 8 * 3 = 24, we can solve for x in the equation 5x = 25 by dividing by 5. Oh how much I took division for granted…

Finite Field Crash Course

In modern day cryptography, most math is done in finite fields. This gets really funky really fast. When working in a finite field, we essientially restrict ourselves to a certain subset of numbers. As a simple example we can use the finite field of 12. There are many ways we can think of math in a finite field, but as a visualization we can think of this as doing math on a number line that has been contorted and bent into a circle. If we add enough to one number we end up back where we started. As rediculous and abstract as this starts to sound, there is actually a very classic example that almost everyone will be familiar with… the standard system of time! Say it is 11am, and 3 hours go by. Then it must be 2 PM. To represent this event mathematically, it only seems natural that we start with 11, and add 3. So 11 + 3 is… 14. It just doesn’t work using our standard system, so what is sad mathmatician to do. The answer is to imagine the numberline the exact same way as the clock, in a circle. If the hour hand starts at 11, and moves 3 ticks around the circle, it ends up back towards the start of the circle at 2. See what I mean by circular number line. Its just like a clock. Now with this new version of addition 11 + 3 = 2. We say that in the finite field of 12, 11 plus 3 is 2. We can generalize this idea to any number. In the finite field of 5, 3 + 3 = 1. Think of a clock with only 5 hours on it. If we start at the 3 tick, and move 3 ticks clockwise, we end up back on the 1 hour mark. All operations we are familiar with in typical math can be performed in these finite fields. As you have seen above the results become alot more complicated and harder to work with, and this added complexity is a good intuition for why certain problems, like working with elliptic curves in finite fields, are very hard to solve, even for a computer. I mean image a simple algebra problem in the finite field of 12, x + 1 = 2. If we imagine this with our clock analogy, we want to know how much time passed previously where when we add one hour, it becomes 2 o’clock. The first solution that comes to mind is 1 of course. If it is 1 o’clock and an hour passes, it’s 2 o’clock. But what if x=13, meaning 13 hour past from the start of a day, then one more hour passes. Well that would be a total of 14 hours passed, or 14 ticks clockwise on the clock. If we start from the start of the clock that also ends us at 2. Same if x=25, or x=37. Overall there are actually an infinite number of possibilities that x could be. As expected this makes everything harder.

Back to ECC

So now we are ready to talk about some ECC basics. Primarily the equation that defines an elliptic curve. This is $y^2 = x^3 + ax + b$. This is what a and b in the challenge file are. They are the parameters that define the specific curve we are working with. We see in the challenge file that secret = (str(a) + str(b)).encode(). This means that if we know the curve parameters a and b, we could get the secret. The key here is that they give us a point on the curve. It turns out that two points fully define the curve allowing us to solve for a and b. Unfortuneatly though, we only get one point. So how do we solve this challenge? Well it turns out that getting a point may not be enought to fully define the curve, but it does allow us to narrow it down enough to just try all the possibilites and see which one gives us the flag.

Mathing the Solution

Given that we know point on the curve, we can look at the equations for elliptic curves to get some very usefull information. Call our givin point $G = (x, y)$. We know then from the general elliptic curve equation that $y^2 = x^3 + ax + b$. If we shift some stuff around we get that $ax = y^2 - x^3 - b$. Remeber all these equations are in the finite field of $p$, so we can’t just divide by $x$ to solve for $a$. Instead we have to multiply by something called the modular multiplicative inverse of $x$, which we write as $x^{-1}$. Luckily when using sage, if we tell it that $x$ is in the finite field, if we try to multiply by $x^{-1}$, sage will calculate this special number for us. So then $a = x^{-1}(y^2 - x^3 - b)$. This is great but we need $a$ and $b$. If we look very carefully at how $a$ and $b$ are generated, we see that $a$ is between $2024$ and $2^{32}$. This number is possible to bruteforce, but it would take a really long time, and its possible it wouldnt be found by the end of the competition. $b$ however is generated as a number between $2024$ and $a$. This means that there are likely to be far fewer possiblilites for $b$. We also recall that from the above we have enough information to calculate $a$ from $b$. So we just need to try values of $b$ and their respective values of $a$. If we ever decrypt the ciphertext successfully, we know we have found the right curve parameters and the challenge will be solved.

Bruting the Force

Ok so to get this done I started by writing a sage math function to test some given $b$ value to see if it leads to the correct curve.

I first defined the given information as well as x_inv which will be the $x^{-1}$ value in our solution.

G = [47955680961873936976498017250517754087050557384283400732143179213184250507270, 29032426704946836093200696288262246197660493082656478242711220086643009788423]

p = 61858486249019152861579012404896413787226732625798419511000717349447821289579

F = GF(p)

ct = b"\x18\xf4$\xf1\xe5WA[\xf2P\xfa\xfcEE\t\xed\xe2m\xaf\xf6$K\xf6\xae\xd9K\x81\x95D\xe3`W\x8f\x04\xfbI\xe5\x06\xd3\xe9\x1a\x1e\x16\xfbZ\xe6\xd2\x06\xd6o|#ns'm\x12\x96\x1d\x8d\xd1\xbd<\xd9\x1dy\x0b\xa95i\xfds\x86|\xad\x92\x88\xa7\x07="

iv = ct[:16]

ct = ct[16:]

x = F(G[0])

y = F(G[1])

x_inv = x^-1

Now we can write the function

def test_b(b):

a = (y^2 - x^3 - b) * x_inv

secret = (str(a) + str(b)).encode()

key = hashlib.sha256(secret).digest()[:16]

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv=iv)

pt = cipher.decrypt(ct)

if b'SIVUSCG' in pt:

return pt

return ''

This function uses the given b along with the other challenge information to calculate the respective a value. Then it recreates the secret using those values, and then the key using the secret. Then it attempts to decrypt the ciphertext with the solved key and if it looks like the flag, we return the decrypted value, otherwise we just return a blank string. The first thing I then setup was just a for loop to call test_b for every possible b value and stop when we get the flag.

if __name__ == "__main__":

for b in range(0, 2^32)

print(f"Trying b = {b}")

result = test_b(b)

if result:

print(result)

break

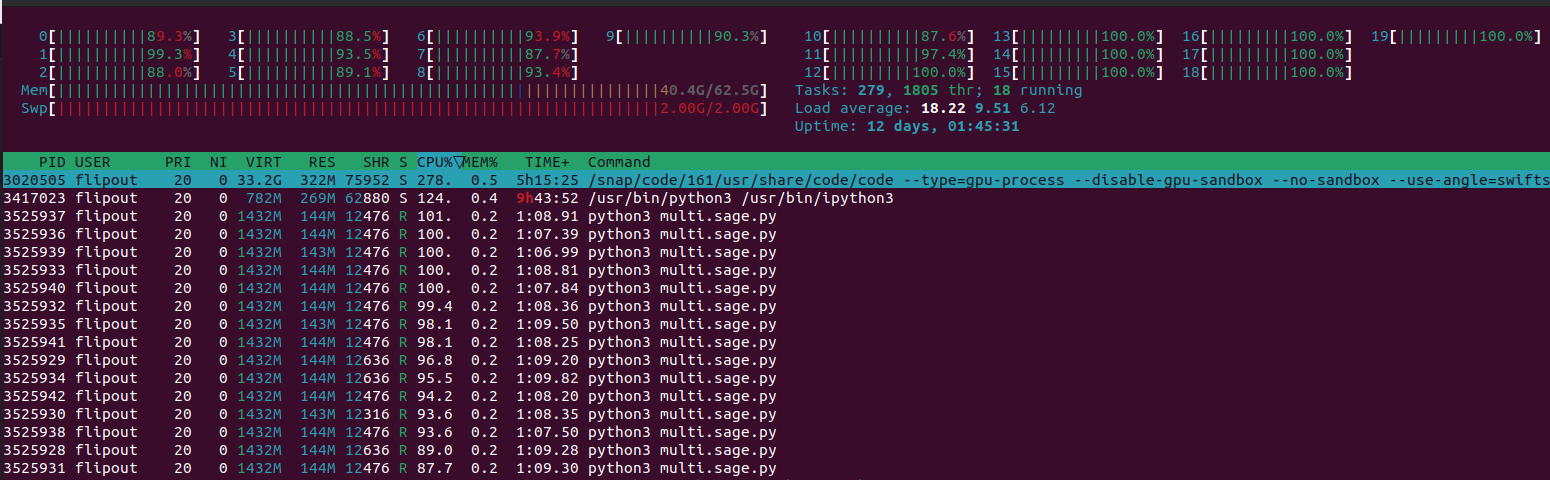

I realized pretty quickly that this was going to take waaaaaayyyyyyyy to long. This confused me because I have a pretty beefy laptop, and it shouldve been able to try numbers so much faster. Then I used the htop command on linux, which allows you to visualize your CPU usage. Then it all became clear. One of my 20 CPU cores was at 100% usage, and literally everything else was hovering around 5-20%. This is because only a single process, in this case my bruteforce script, can only run on one core. This means that if I want to utalize all the cores for this task, I need to write a program that breaks into multiple processes so that the work can be divided on multiple cores. This type of program is called a multithreaded program. In my coursework, this has been covered for the c programming language but in this case I was using python, so I decided to go down the rabit hole of finally learning how to use multithreading to speed workloads like this up. I knew this was a good investment of my time because this is by far no the only time this exact situation has come up during CTF and Ive even dropped point because I didn’t just suck it up and learn python multiprocessing. Turns out its far easier than I imagined because python takes car of most of the heavy lifting. Enter the python multiprocessing library.

Python Multiprocessing

So python’s multiprocessing module allows us to divide a workload into any number of concurrent processes. This can be accomplished using the multiprocessing.Pool(). There are many different ways we can use a pool, but for a simple case like this where we need to crank through a bunch of options, we can use the Pool.imap_unordered() function. This allows us to apply a function, in our case test_b to some iterable, which for us is the range of possible b values. It takes in chunksize which allows us to specifiy how many numbers are given to a process to work through. This kind of chunk based multiprocessing works great when the individual task is far too small to get its own process. For us, testing a single b value is an incredibly fast task for a computer, so giving each process its own b to test is very inefficient because the time it takes to startup and end that process is likely more computationaly expensive than the actual task itself. With this setup we can give each process its own chunk of b values to test at a time. Our revised program will look like this:

if __name__ == "__main__":

vals = range(0, 2^32)

with multiprocessing.Pool(15) as pool:

for i in tqdm.tqdm(pool.imap_unordered(test_b, vals, chunksize=500000), total=len(vals)):

if i:

print(i)

pool.terminate()

break

First we define vals which is the list of values we want to perform computation on. Then we define our multiprocessing pool as pool and tell it that we want it to use a maximum of 15 processes. Then we can define a for loop using the imap_unordered which will divide the workload into chunks of the defined size and run our function on each of those chunks concurrently. The body of the for loop defines what each process will do after it finishes applying the test_b function to one of its designated values. Here we check the return value of the function, stored in i, and if it is anything other than an empty string, which if you remember in our case means we decrypted the ciphertext to a plaintext matching the flag format, then we print out that decrypted text and call pool.terminate() to tell all the processes to shutdown early since we have what we need. The whole tqdm.tqdm() is just a way to display a progress bar to the console while our worker processes complete chunks. Now when I run this program and run the htop command all of my cores are sitting at 95-100% usage. We can also see in the process list that there are many different copies of the program running.

Of course as a result of this added horsepower, we crank through values sooooooo much faster, and within a few minutes the flag pops up in the console and the program terminates! Judging by the flag I suppose the intended solution has to do with the flag length, but a flag is a flag.

Flag

SIVUSCG{ICANMAKETHISFLAGASLONGASIWANT...YEAHHHHHH}